|

Origin of the LOTUS LEAF WORKS

Original lotus leaf works

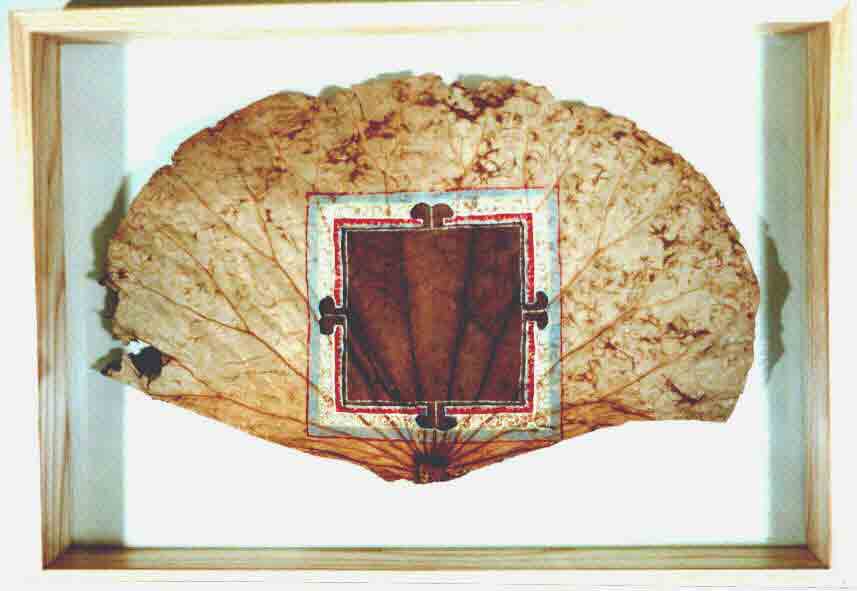

In 1997, while in MFA studies at School of Visual Arts, and while somewhat "burnt out" in my studio at school, I began to paint on lotus leaves in my home studio. Since I did not think my advisors would be impressed by this new direction, and since I too was not sure whether this was just a clever gimmick or something I could truly explore, I did not reveal this work to anyone at school. However, one of my advisors happened upon a painting of Medicine Buddha that I had brought to school and became very interested in what I had been doing on my own. Ultimately, these lotus leaf paintings, this outside project, would become the main focus of my Master's thesis in 1998. The image to the right, "Tathagatagarbha," is the third lotus leaf painting I ever did after a Medicine Buddha and the Mayadevigarbha featured on the home page.

|

|

Painting on the Lotus Leaf

The idea of painting on leaves is ancient indeed. Paper itself was adapted to replace actual vegetal manuscripts and we still call a sheet of paper a "leaf" of paper as a result. Our word for paper comes from papyrus which is a plant pressed into sheets for writing on. So plants were one of our first, most portable writing surfaces. The decision to paint on the lotus leaf was for manifold reasons but brought some unique problems which is why no one seems to have attempted it before, even in India, land of the lotus AND the palm leaf manuscript. As a water-repellent leaf, ink rolls right off the leaf when wet and if you get it to dry in place, it will flake off when it dries. One cannot plan or draw on the dried lotus leaf with a pencil because the hard, sharp point will poke a hole in the surface before it succeeds in making a mark. Therefore, the image must be totally composed in the mind before making the mark and the mark must be made directly in the final pigment, gouache/tempera. Making these images for myself, I would not care to preserve them. But knowing they are for sale, naturally urges me to box-mount them in a frame right after completion. For the sake of the collector, I have even taken to spraying the works with preservative solution, but this to me goes against the spirit of Impermanence that these works are done in. Either way, they would last roughly a person's lifetime, but I anticipate that if they weren't framed they would be gone in 100 years. That was my original intention and my very point. I have no investment in Occidental notions of forever and ever. These are views that Buddhism notes as fallacious. The image right-above, "Bardo" is a tribute to Ksitgarbharaja Bodhisattva who took a vow to dwell in hell until he emptied it of evil-doers by dispelling their erroneous views and habits. The magnitude of his vow is a great inspiration for Buddhists in that it puts our relatively tiny vows in perspective. The image describes a person meditating through death, remaining ever vigilent. The image also references the tales of Buddhist masters meditating up until the time of their death and past that into the Bardo or time in between incarnations.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|